Produced on behalf of the British Association of Sport and Exercise Sciences by Dr Charles Pedlar, Prof Greg Whyte FBASES, Dr Jack Kreindler, Sarah Hardman and Prof Benjamin Levine

Background and evidence

Over 35 million people travel to high altitudes (>3,000m) each year with a greater number travelling to moderate altitude (1,500m – 3,000m) including elite athletes undertaking training or competition (Wilber, 2004). Altitude (i.e., hypobaric hypoxia; HH) results in arterial hypoxemia (low blood oxygen) due to a reduced barometric pressure and an unchanged fraction of inspired oxygen (FiO2; ca. 21%). Simulated altitude (i.e., normobaric hypoxia; NH) results in arterial hypoxemia due to a reduced FiO2 with an unchanged barometric pressure. Commercially available NH environments, such as altitude chambers and altitude tents, control FiO2 via nitrogen dilution where nitrogen is added to ambient air reducing the FiO2. It is generally accepted that the physiological response to HH is the same as NH at moderate altitude, however; there are few empirical data to support this hypothesis. There may be differences in responses at high (3,000m – 5,400m) and extreme (>5,400m) altitude particularly associated with the incidence of high altitude pulmonary oedema (HAPE) and high altitude cerebral oedema (HACE; West et al., 2007).

Exercise capacity diminishes with ascent to altitude, associated with a reduced arterial oxygen pressure (PaO2) evident in a haemoglobin desaturation (SaO2). Hypoxia Inducible Factor 1 alpha (HIF1-α), is stabilised in hypoxia signalling a downstream cascade of responses, including erythropoiesis, angiogenesis and metabolic reprogramming (Semenza, 2009). These adaptations improve hypoxia tolerance and may enhance sea level endurance performance in some individuals. Limited data exist demonstrating positive adaptations to strength, power and anaerobic capacity as a result of a hypoxic intervention.

A number of deleterious effects result from a reduced PaO2 including Acute Mountain Sickness (AMS) characterised by a spectrum of maladaptive responses from minor (i.e., headaches, sleep disturbance, anorexia, sunburn and dehydration) to the potentially fatal HAPE and HACE, usually at higher altitudes (West et al., 2007).

Altitude training

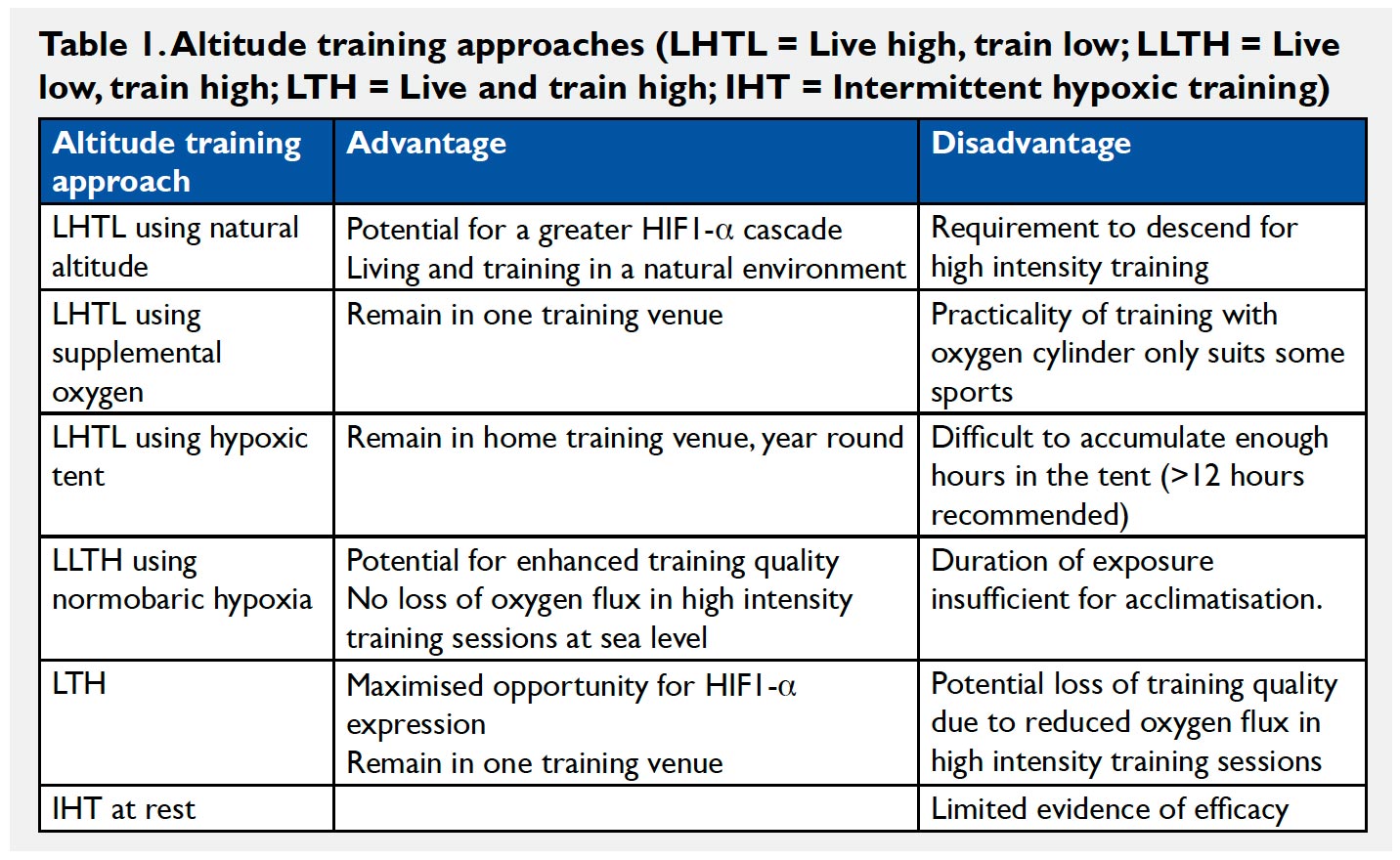

Common altitude training practices amongst athletes include: living and training high (LTH); living high and training low (LHTL) in order to maintain training intensity; living low and training high (LLTH); and intermittent hypoxic training at rest (IHT; Wilber, 2004; see Table 1). These paradigms can be achieved with natural altitude, simulated altitude, or a combination.

Pre-ascent evaluation

Pre-ascent evaluation should include iron status, primarily ferritin although a comprehensive screen would include other measures such as transferrin receptor (Suominen et al., 1998) and total haemoglobin mass measured by carbon monoxide rebreathing (Schmidt & Prommer, 2010). Exercise responses in NH (lactate, heart rate and oxygen saturation via pulse oximetry) can identify those athletes who are likely to cope well at altitude. Those with the greatest decline in performance and peripheral oxygen saturation during heavy exercise in acute hypoxia are most likely to suffer losses in performance at altitude. This knowledge may be particularly useful for those travelling to high altitude.

Acclimation and acclimatisation

Simulated altitude facilities are useful for acclimating individuals prior to ascent, either through exercise or sleep. In athletes, the duration of time exposed to NH is crucial in the use of sleeping

devices with a critical duration of at least 12 hours/day. Some protection from AMS is possible with shorter duration exposures. Limited evidence exists for the use of IHT for acclimatisation or performance enhancement (Levine & Stray-Gundersen, 2006). Short term acclimatisation (primarily ventilatory) occurs over 5-7 days at moderate altitude, although adaptations will continue to occur over a number of months. To ensure an adequate erythropoietic response to altitude, at least 3 and preferably 4 weeks of exposure is recommended. Iron status assessments should be repeated at altitude to ensure they remain unchanged.

Management of training volume

Exercise responses are disrupted at moderate altitude such that a leftward shift in the lactate curve and raised heart rate are observed, gradually returning to baseline (sea level) values with acclimatisation. To avoid over-reaching, athletes must reduce training intensity during the initial 7-10 days at altitude. Other factors must also be considered, for example, extended journey time to reach altitude training venues resulting in fatigue.

Biomechanics

Faster sprint speeds are experienced and this may be a desirable feature of training at moderate altitude for anaerobic individuals. The trajectory of projectile objects will be affected by HH and the athlete will need to adjust their technique in order to compensate for this, adjusting it again upon return to sea level (Chapman et al., 2010). Furthermore, athletes who time their inspiration and expiration according to their stroke, e.g., swimmers, canoeists and rowers, will have to adjust their timing at altitude because of a relative hyperventilation.

Sleep

Some athletes (25-35%) will experience sleep disruption caused by periodic breathing resulting from the interplay between hypercapnia and hypoxia leading to central sleep apnoea. This improves or disappears with acclimatisation. Global sleep quality can be monitored using actigraphy, sleep questionnaires and other sleep monitoring devices. However, to identify periodic breathing and sleep architecture, more intensive monitoring tools can be employed (i.e., polysomnography; Pedlar et al., 2005). At moderate altitude sleep should improve over 2-3 nights, although, profound sleep disruption may be experienced at high altitude, which may not improve with acclimatisation depending on the altitude and the individual.

Acute mountain sickness

Some athletes at moderate altitude may experience symptoms of mild AMS (i.e., headache and nausea), but this is rare and generally self-limited. Although this can impact upon training during the first few days at altitude, it is rare for symptoms to be sustained or get worse while remaining at the same moderate altitude. At high altitude AMS is common and exacerbated by exertion. Paradoxically, gains in aerobic capacity prior to ascent fail to offer protection from AMS. Symptoms may include headache, nausea/vomiting, fatigue/malaise, dizziness and sleep problems or insomnia. These can be assessed using the Lake Louise Questionnaire. Secondary to AMS are the more severe conditions of HACE and HAPE, which are both potentially life threatening and these should be referred directly to a doctor (West et al., 2007). Individuals travelling to high altitude without a doctor present should learn the signs of AMS, which are described extensively elsewhere (Imray et al., 2010), in order to self-diagnose and treat accordingly. Treatment is rapid descent, however prophylactic administration of Acetezolamide and Dexamethasone (banned substances for athletes) are effective, when taken 24 – 48 hours prior to ascent. This applies to individuals going to high altitude (>3,000m).

Other issues

Dehydration is common at altitude, caused by sweating and fluid loss through the upper airways due to increased ventilation. The atmosphere offers less protection from UV radiation, thus sunburn occurs more rapidly than at sea level. Weight loss has been observed at altitude, which may be caused by a loss of appetite, or a change in energy balance (either because of changes to energy expenditure or food availability).

Performance post-altitude

The optimum time to descend prior to competition is poorly understood. Studies suggest high quality performance is sustained at sea level for 3-4 weeks. LHTL athletes may have substantial improvements even in the first few days after return, however this may be more variable. It is known that upon removal of the hypoxic stimulus, a reversal of some altitude-specific adaptations occur rapidly (i.e., neocytolysis, red blood cell destruction), and the entire acclimatisation response is mostly undetectable after 4 weeks at sea level. Acid/base balance is acutely affected by the return to sea level with potentially negative performance implications. At altitude, respiratory alkalosis results in a loss of bicarbonate, which must be restored in order to effectively buffer acidosis during high intensity exercise. This is somewhat variable between individuals but may take up to a week to fully restore.

Conclusions and recommendations

• Altitude training offers a natural method of potentially enhancing performance.

• Individuals should be assessed and educated on the effects of altitude before travelling.

• Pre-acclimation is recommended prior to travel to moderate and high altitude to reduce training disruption in athletes and AMS in climbers.

• Disrupted training and recovery are expected at altitude, requiring careful management.

• At high altitude, AMS is common, potentially worsening to HAPE or HACE, all of which should be assessed and treated by a doctor. If no doctor is present, individuals travelling to high altitude should be educated in the signs, symptoms and treatment of AMS.

• Other problems such as sunburn and dehydration should be avoided.

Dr Charles Pedlar

Dr Charles Pedlar is a BASES accredited sport and exercise scientist and Director of the Centre for Health, Applied Sport and Exercise Science (CHASES) at St Mary’s University College.

Prof Greg Whyte FBASES

Prof Greg Whyte FBASES is a BASES accredited sport and exercise scientist at Liverpool John Moores University and 76 Harley Street.

Dr Jack Kreindler

Dr Jack Kreindler is the Medical Director and high altitude medicine specialist at 76 Harley Street.

Sarah Hardman

Sarah Hardman is a BASES accredited sport and exercise scientist and physiologist at the English Institute of Sport at Bisham Abbey (GB Rowing).

Prof Ben Levine

Prof Ben Levine is the Director of the Institute for Exercise and Environmental Medicine, University of Texas in Dallas.

References

Chapman, R.F., Stickford, J.L. & Levine, B.D. (2010). Altitude training considerations for the winter sport athlete. Experimental Physiology, 95, 3, 411-421.

Imray, C., Wright, A., Subudhi, A. & Roach, R. (2010). Acute Mountain Sickness: Pathophysiology, prevention and treatment. Progress in Cardiovascular Diseases 52, 467–484.

Levine, B.D. & Stray-Gundersen, J. (2006). Doseresponse of altitude training: how much altitude is enough? Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology, 588, 233-47.

Pedlar, C., Whyte, G., Emegbo, S., Stanley, N.,

Hindmarch, I. & Godfrey, R. (2005). Acute sleep responses in a normobaric hypoxic tent. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise, 37, 6, 1075-1079.

Schmidt, W. & Prommer, N. (2010). Impact of alterations in total haemoglobin mass on VO2max. Exercise and Sports Science Reviews, 38, 2, 68-75.

Semenza, G.L. (2009). Regulation of oxygen homeostasis by hypoxia-inducible factor 1. Physiology, 24, 97-106.

Suominen, P., Punnonen, K., Rajamaki, A. & Irjala, K. (1998). Serum transferrin receptor and transferrin receptorferritin index identify healthy subjects with subclinical iron deficits. Blood, 92, 2934-2939.

West, J., Schoene, R. & Milledge, J. (2007). High altitude

medicine and physiology (4th ed.). London: Arnold.

Wilber, R.L. (2004). Altitude training and athletic performance. Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics.

First published in The Sport and Exercise Scientist, Issue 30, Winter 2011. Published by the British Association of Sport and Exercise Sciences – www.bases.org.uk

Add comment